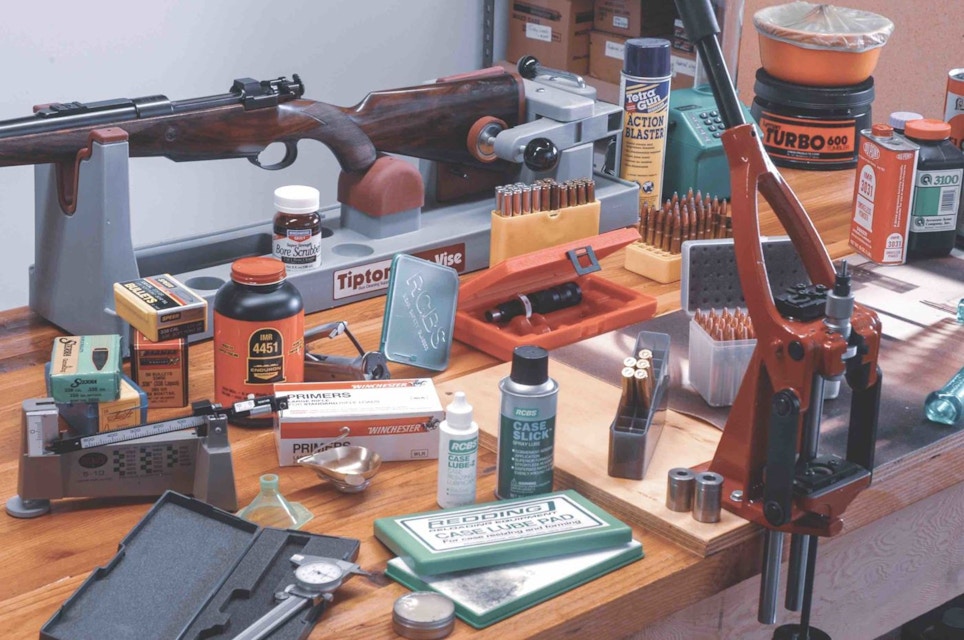

Keep a neater bench than this, stocked here to show the variety of items that can profit your gun shop.

Heavy enough to anchor a small sloop, a Herter’s C press cost $15. Could I ever save that much by handloading? I took the chance. Dies and a keg of surplus H4831 left me with a choice: bullets or rent.

Fifty years later, my fortunes have improved, and that press is still chugging out cartridges.

Handloading does more than put shekels in your pocket. It’s a personal investment that increases the satisfaction you get from each shot. It puts you in company with legions of the like-minded: shooters, but also engineers behind the tools and wildcatters who use them to make new cartridges. Handloading brings you ammo in pieces. Assembling them, then testing loads, you join people doing more with rifles than simply pulling triggers. They’re students, experimenters, amateur ballisticians; handloads distinguish the committed from the dabblers.

You might mention that to your customers, if you’re prepared to supply them as handloaders, and perhaps bring more into the fold with in-shop demonstrations.

Gun-shop owners and companies that manufacture tools and components tell me the handloading market is resilient and has remained strong when rifle sales slump. The tsunami of new factory loads over the last couple of decades has blessed the handloading market with myriad bullets and powders for shooters to try. Sophisticated new tools, from electronic scales and concentricity gauges to progressive presses, give you plenty of things to sell.

But aren’t current factory loads much improved? Certainly! The 1959 Shooter’s Bible featured 78 Winchester and Remington loads in its rifle ballistics table. Hornady’s current ammo roster lists over 265, with 18 for the .308 alone! In-flight and on-target behavior are tuned to the task, from steel plates furlongs distant to sedan-size creatures a few hoofbeats away and coming.

Of course, top-tier factory loads are priced accordingly. You can’t tweak them to wring all the accuracy or ballistic romp your rifle has to offer. Also, factory fodder doesn’t feature every long-range and heavy-game bullet. To get the most ammo options, you must handload.

Light demand for some cartridges has left them with factory loads from the Pleistocene. Others have been blessed by evolution in bullets and powders. Example: Poor accuracy from commercial .250 Savage ammo sent me to the bench. Handloads with 87-grain Sierras reduced group sizes from 2.4 MOA to .6 MOA! Handloading can also add spunk to cartridges designed for relatively weak actions. The .45-70, for example, has been throttled by its original home in the 1873 Springfield. Handloaded for stronger guns, it’s a beast.

Handloading requires time and study. You get 24 hours each day. Study is simply an extension of passion, often sparked by hands-on experience. You can set up a press with a sizing die in a small space. A lube pad and a few fired cases will let customers feel an old hull made fresh. Add a priming tool, seating die and bullets, and you can walk them through the entire process. Handloading is like shooting: You can describe it; but words can’t impart that feel.

Loading manuals are must-reads, and not just for beginners. I have more than 30 within easy reach. After a half century of handloading, why so many? New cartridges, bullets and powders yield new data, and savvy handloaders consult multiple sources.

Manuals provide cartridge dimensions, test-barrel lengths and rifling twist, bullet sectional densities and ballistic coefficients, results of penetration trials, and even the histories of cartridges, components and companies serving handloaders. Manuals are no longer the spiral-backed notebooks of my youth: they’re hard-bound, profusely illustrated volumes thick enough to stop bullets. Three on my shelf — Berger, Hornady, Nosler — average about 1,000 pages. Such treasure troves in gun-shops sell even to customers not yet handloading.

As a car lot crammed with shiny new vehicles draws the eye, so does a gun shop with full shelves and hangers keep customers browsing — and buying. Beyond costly progressive presses, handloading tools include affordable items that entice newbies and veterans alike. An electronic scale is an upgrade for someone like me, who’s used an Ohaus balance-beam for decades.

Powder funnels, case and primer trays, gauges of all types and consumables like case lube move easily. Dies? You can’t stock ’em all, but you can offer to order any. Give customers quick turn-around and reasonable discounts on hardware, plus an assortment of bullets and powders, and they’ll visit often. Unsure about which items to carry? Ask customers before you get stuck with slow movers or run out of top sellers.

To peddle more than entry-level products, you’ll offer know-how that’s hard to access online. While the basics of handloading are well covered in most loading manuals, newbies still need counsel: What’s headspace? What’s the difference between H4350 and IMR 4350? For long shots, should I use 115-grain Berger VLDs in my .240 Weatherby? You’ll also be tapped for tips. Here are a few from my notebook.

Reloading Tips

Know the signs of excessive pressure and adjust handloads right away to avoid it. Difficult extraction and primers with flattened edges tell you to back off! Extruded primers, with a lip around the striker dent, often indicate high pressure but can also mean the striker hole in the bolt face is oversize. Measuring case head expansion is a useful way to read pressure.

Markedly reduced charges of slow-burning powder have produced detonations, the prevailing theory is that primer flame jets across a charge in a horizontal case, igniting it from both ends so pressure curves join near the middle. For reduced charges, consult the manuals. Use reasonably fast powder with a filler like corn meal in front of it.

Keep cases trimmed! A case too long can jam against the chamber mouth, then pinch the bullet as you lock the bolt. If the case mouth won’t easily release the bullet, pressures can spike. Trimming cases a bit shorter than necessary does no harm and gives you more reloads between trims. Exception: straight-walled cases that headspace on the mouth must not be trimmed short!

Adjust neck-size only when handloading for one rifle. Set the sizing die a penny’s thickness below the shell-holder. You’ll reduce “working” of the brass and increase case life.

Seat bullets .1 from the lands so the bullet can move before contacting them, keeping pressure in check and ensuring easy extraction of loaded rounds. Minimal clearance usually delivers best accuracy. If you don’t have a gauge, seat a smoked bullet out and chamber it. Feel for resistance and inspect the bullet for rifling marks. Seat it incrementally deeper until none appear; then seat .1 deeper.

Check for function with hunting loads by cycling them from the bottom of the magazine. Once, after loading early square-nosed Winchester solids for my .375, I got into a running battle with a buffalo. To my chagrin, I later found cartridges pressed into the magazine jammed on its curved face!

Safety First

Like racing motorcycles, sky diving and snorkeling with sharks, handloading is not as dangerous as it might appear to the uninitiated. The IQ of a plow horse will suffice. But lose concentration, and you imperil your shooting career. Keep these caveats in mind:

Secure your loading room — priming compound is an explosive. Smokeless powder burns so fast it can literally kill in a flash. Keep both away from the hands of innocents and dullards.

At the bench, admit that no matter how long you’ve been shooting, you do not know all there is to know about handloading. Focus on the job. Limit yourself to one powder canister and one box of bullets within reach at a time. Store components in original containers. Bullets scant thousandths bigger than on the label can hike pressure. A fast-burning powder mistaken for a slower fuel can burst your rifle.

Label every box of handloads with age-resistant ink. When working up several loads for one cartridge, color-code them with a dab of marker on each primer and record the codes in a notebook.

If a cartridge won’t chamber easily, extract it, check the bullet for rifling marks and measure the case to ensure it’s at or under SAAMI length. A snug fit at shoulder, belt or rim (minimum headspace) isn’t dangerous. But before you lean on that bolt handle to close it, figure out what’s tight.

Discard cases showing incipient separation, typically a white line in front of the extractor groove, where the web tapers thin. You’ll get stretch here as the brass flows forward with each shot — more with belted hulls in generous chambers. Firing “work hardens” brass; a thin spot becomes a point of separation. Escaping gas can then wreck your rifle and leave you blemished. Always discard visibly tired brass.

Unless you crave quality time with your attorney, do not sell or donate your handloads to anyone. Your pet 7mm-08 loads become bombs when the unwitting thumb them into a .25-06. A friend grabbed a box of .308 loads one morning to check zero on a fine .270 I’d sold him. The hull was, of course, short for the chamber; it slid right in. Pressure swaging the .308 bullet to .277 tore the rifle apart.

It would also be smart to avoid handloads assembled by someone else. Once, at a range, I agreed to fire a pal’s mid-level handloads in his lever rifle as he watched. The cases extracted easily. We chatted briefly, then I turned back to the target, thumbed the hammer, aimed and squeezed. Clack. I waited several seconds before opening the action, in the event of a hang-fire. When I dropped the lever, an empty case tumbled out.

“I must have forgotten to cycle.” I chambered another round and prepared to fire again. Then an angel tapped me on the shoulder. There was one other possibility. Dropping the lever, I looked into a muzzle black as a coal shaft at night. I had not forgotten to cycle. The “empty” had been a primed case with a seated bullet but no powder. When I triggered that shot, the primer pushed the 200-grain softnose into the bore, where it lodged just ahead of the throat. The primer’s report couldn’t escape case or bore and was further muffled by the hammer fall. Had I fired a second cartridge, its bullet would have crashed into the lodged bullet near the peak of the pressure curve, almost surely shredding the rifle and my left hand — or worse.

Handloading under stress or a tight deadline causes mistakes. A Navy report after the Civil War noted that of 25,476 muzzleloading rifles found on battlefields, “at least 24,000” were loaded, with half containing “two loads each, one fourth from three to 10 loads each.” Many held “two to six balls … with only one charge of powder. In some, the balls [were] at the bottom of the bore with the charge of powder on top….” One barrel had 23 loads stacked atop each other.

If you lack the time or presence of mind to pay attention, your handloads will show it!

Enough caveats. Sensibly done, handloading is safe, fun and economical. It gives you options in ammo that can trump even the best factory loads. It’s a step to wildcatting. It puts you in good company. Veteran handloaders know all that. Setting up a press in your shop will prompt the uninitiated to ask questions, then try handloading. They’ll remember where they got counsel, tools and components!

Sidebar: Handloading for the Long Poke

Marksmanship determines reach. Accurate, flat-shooting loads extend effective range only to the limits of your ability to hit. At distance, uniformity is crucial. Uniformly good shooting matters most, but I’ll get off that horse to review how top shooters reduce variables in their ammo:

Long-range competitors sort cases by make and weight, even by lot. They turn necks to the same wall thickness and outside dimension, clean primer pockets, ream flash-holes to the same diameter. They trim hulls to the same length, just short of SAAMI spec, and chamfer the mouths. To extend case life and ensure snug fit in the chamber, they neck-size only.

Finicky shooters try several primers before choosing one. Magnum Rifle primers deliver a longer flame; they’re not necessarily hotter. I use them for powder charges of 65 grains and up — in other words, slow propellants in big cases. Hand-priming helps ensure uniform seating.

The high ballistic coefficients of long-range bullets come at a price. Long noses and tapered heels make these heavy missiles so long that they may not function in ordinary magazines or throats. They may require extra-steep rifling twist to stabilize. Thin-jacketed hollowpoints so accurate at distance don’t reliably produce lethal wound channels in big game. Stronger jackets, bonding and mid-section dams help ensure adequate penetration up close. At distance, deceleration impedes upset, no matter the bullet design. Most hunting bullets will expand down to impact speeds around 1,600 fps. Few loads bring that velocity with lethal punch past 700 yards. Bullet-makers are working to broaden velocity windows.