Most customers don’t consider the technical details involved in accurate shooting. They are used to picking up a rifle, pulling it naturally into their shoulder, and assuming it will be properly aligned for accuracy. If the rifle has a scope, it adds to their confidence. They might even mount a scope themselves in the false belief that accuracy will automatically improve, and then become frustrated on their first trip to the range. This is where you become a valuable resource.

Have you ever shouldered a scoped rifle and found that the reticle didn’t appear level? When this happens, the gun or scope is said to be canted (tilted) to one side or the other. Regardless of the cause, it’s unsettling because we intrinsically know that accuracy will be affected. Let’s learn what happens when a rifle is canted to one side or the other. But first, let’s take a short detour and look at gravity.

I’m sure that Sir Isaac Newton had seen plenty of apples fall from trees. It’s a natural happening that usually doesn’t inspire much interest. But one such sighting caused Newton to change how he viewed the world. I recall learning in school that an apple fell and hit him on the head, and that’s what started it all. I’m not sure if the story is true, but Newton did mention in his notes that it was a falling apple that started his examination of gravity and its effect on objects. We’ll not delve deeply, but we must understand the effect gravity has on objects — specifically bullets fired from a gun. I promise there’ll be no math involved.

If we held a rock at arm’s length and dropped it, it would fall predictably to the ground. We’ve all done that. The force that pulls the stone to the ground (gravity) is uniform, consistent, and can be easily calculated. We can do the same thing with a bullet as easily as a rock, and it doesn’t matter if the bullet has a forward motion. The bullet starts falling as soon as it leaves your hand or exits the barrel of a gun.

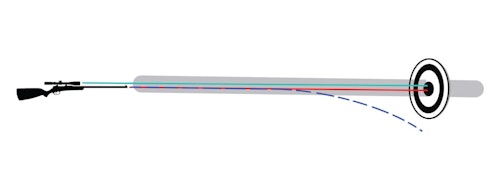

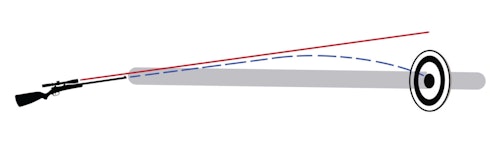

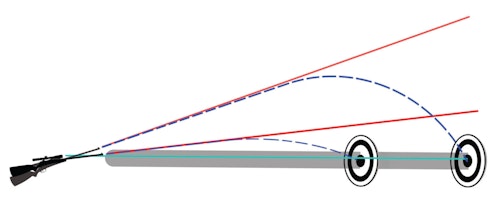

Diagram 1 shows what would happen if the rifle barrel was held parallel to the ground. The bullet exits the barrel and begins falling. That’s not good if you’re trying to hit a target some distance away. To compensate for the effects of gravity, we must incline the barrel upward so that the bullet’s path forms an arc. (See diagram 2.) The red line represents where the barrel is pointing. In this case, it is inclined above the target so that the bullet will fall and hit the target. The angle of that incline depends on the distance to the target. (See diagram 3.) Targets farther away require more rise. When a rifle is zeroed at a certain distance, this incline is what’s being adjusted.

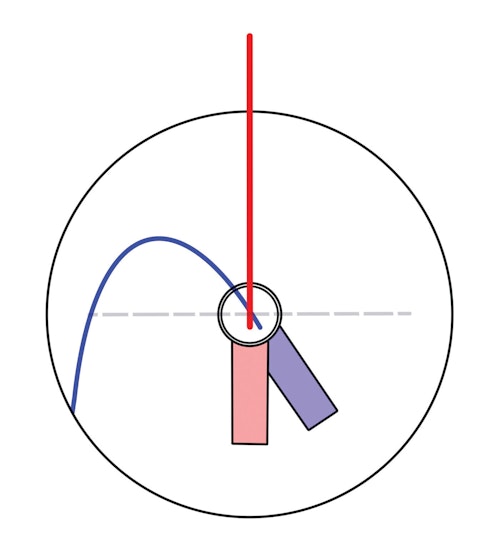

Let’s examine the bullet's arc once fired from the rifle. Diagram 2 illustrates the arc viewed from the side. This is true whether, or not, the rifle is canted. The bullet rises until it reaches the apex of the vertical trajectory, then begins to fall. If the rifle is aligned perfectly, the view from behind the gun will show the bullet rising perpendicular to the ground and falling along that same line. See the red trajectory in diagram 4. This is what we depend on for precise shot placement.

The Effects of Cant

Remember that barrel incline? When the gun is canted, the angle no longer points perpendicular to the ground. Now it points up and off to the left. Rather than the bullet rising straight up and falling on the same line as the red trajectory in diagram 4, it now has a second arc as viewed from the rear. See the blue trajectory in diagram 4. The farther the distance to the target, the farther the bullet travels from that center line. Combining both arcs (viewed from the rear and from the side) results in the bullet striking lower and to the left of our intended point of aim.

A 1-degree cant will produce an average of 5 inches of lateral displacement from the point of aim at 1,000 yards. It should be clear, therefore, that eliminating rifle cant is critical for long-distance shots. But what about shorter distances? This is still ½ inch off center at 100 yards. If that doesn’t sound like much, consider how slight a 1-degree angle is. It’s more likely that the angle might be 2 or 3 degrees. The error then becomes much more prominent.

One of the amazing traits of how our mind works is that what we do daily is governed not by conscious thought but instead happens unconsciously. There is an instinctive desire to level reticles that are not aligned properly. If the scope’s cant is minor, we will compensate for it. During this process, our mind assumes that the scope is mounted correctly, so we will slightly adjust our hold to ensure that what we see appears level. But leveling an out-of-level scope can quickly induce that 1, 2 or 3 degrees of rifle cant discussed above.

Alignment is the Key

We’ve discussed how our body’s natural actions can induce rifle cant. What if there’s a way to use those same instinctive actions to our advantage? It’s possible to do that if we ensure the scope is correctly mounted. When the rifle and scope align, the body’s automatic desire to hold things level will eliminate rifle cant. The reticle will be a true reflection of rifle cant. This time, our body’s natural behavior will ensure no cant is involved.

Many people improvise rather than use the correct tools for the job. I know people who do just that when adding a scope, and they swear that their work is as good as if installed by a gunsmith. That’s likely because of the shorter distances they usually hunt. As we’ve seen, the error is small in close and grows as the distance increases. I don’t know a single long-range shooter who will do the same. They realize that scope cant is only one of the many adjustments needed when mounting a scope, and they use the proper tools and techniques.

At Distance

We’ve already mentioned that some people mount scopes “successfully” without using reticle leveling kits then tout their abilities with evidence of animals taken in hunts. They are not doing precision shooting. Let’s face it, a 2-inch variation in accuracy isn’t a problem for them. Nobody will even know their exact point of aim anyway. Plus, many shooters zero their rifles to account for rifle cant. So long as they use a consistent technique, their accuracy will be repeatable. The problem is that achieving that zero will be much more complicated due to the cant.

You’re likely to have a customer argue that rifle cant isn’t that important since it’s common practice for police and other combat shooters to cant their rifles intentionally and that they go so far as to add 45-degree sight mounts on their guns. This overlooks distance. If close-range hunters experience a half-inch impact shift at 50 yards, how much less shift will the tactical shooter experience at 50 feet? Distance is the critical factor. For close combat situations, a red-dot mounted on a canted mount makes little or no difference when engaging a target. Police and military units aren’t aiming at a bullseye target. They aim at a vital “zone” that typically spans about 6 inches. When people are shooting back, speed is more important than precision. Operators use a specific tool for a particular situation. It should be noted that the only reason for using offset sights is to get around a scope, which they have mounted and use for more precise shots.

Understanding what rifle and scope cant and how they affect different shooting activities applies to all customers. It’s most critical, however, for those shooting at longer distances. A customer looking at getting into precision shooting needs to know that a rifle zeroed to hit at 1,000 yards can miss the entire target with as little as a 5-degree cant. Fortunately, you can lead them to the proper tools to set up their rifle. More importantly, you’ll now be able to give them the knowledge to help them become more skilled marksmen.